AI and the Indigent Werewolf

I was asked recently, in an interview as it happens, about the implications of AI for creative writing. Now, there’s so many answers to this and I did my best to articulate a few. And they deserve a post to themselves. But one use of AI is to provide writing prompts. I told AI what my usual writing territory and asked for a prompt from somewhere else. A curve ball. It gave me “The Indigent Werewolf”. So, here it is:

I had seen him three nights in a row, crouched or asleep in the dark doorway of the vacant shop on Silver Place. He wore, despite the unaccountable October warmth, the same thick overcoat, which was made - I could see, beneath the decades-deep dirt, so ingrained it was greasy - of the finest bottle-green moleskin. I was walking back from the University’s twenty-four-hour library, where I had experienced, apropos of nothing a pleasantly private sense of strength.

I cannot explain why I stopped. Perhaps I wished to halt the world by doing something unexpected.

I had three pounds fifty in my pocket, enough for a coffee and a pastry at the all-night café on D’Arblay Street. I approached him and made my proposal. His eyes seemed to reflect more light than that dim street contained. He nodded, and rose to his feet with slow untutored grace. His footsteps made no sound on the pavement; mine were awkwardly loud, for I wore my creaking leather shoes, purchased in a moment of almost lewd extravagance in Milan, that day of the conference. He wore what appeared to be hospital slippers.

We entered the café just as it started to rain.

The place was empty except for a skinny barista who didn’t look up as we came in the door. I ordered coffees and croissants. We sat by the window. Outside, the streetlights made pools of electrical sunrise on the already drenched grey pavement.

“You read poetry,” he said; not a question but a statement. His foreign accent was smoothed – or smothered - by years of speaking English.

“How do you know?”

“I can smell it.”

“Yes, I’ve been reading Crow,” I said, “you know Ted Hughes?”.

“You carry him with you,” he said, tapping his temple with a long, dirty finger

I might have been shocked by this statement, or simply cried “bullshit”, but instead found it perfectly reasonable. Of course this man could smell poetry on me. Because yes, poetry has a scent. Why did I not even know this? This was how I responded. As if I were able to share his senses, or as if pulled into their orbit.

We sat in fraternal silence. He ate his pastry with precision, collecting every falling flake with a moistened fingertip. His nails, I noticed, were unusually thick and yellow, and I found myself staring at his hands, which seemed too large, too applecrushingly large, for his frail and colourless frame.

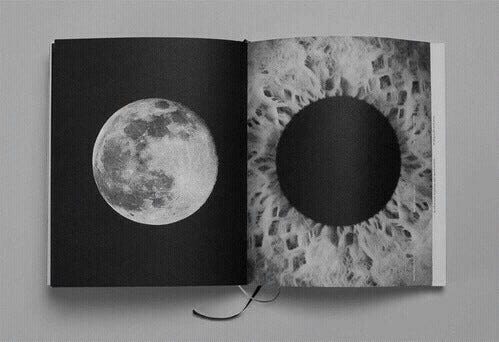

“Do you ever look at the moon?”

“Sometimes,” I answered, “mostly when drunk.”

“Abso-fucking-lootely” he said, the blue eyes brimming with laughter.

“You should look more often. To look at the moon is also to feel, to feel in your body the tug of the moon. In that sense you can’t simply look at the moon, any more than you can look dispassionately from a cliff at rocks far far beneath.

He drained his cup and set it down with a finality that suggested our meeting was winding up.

The rain had stopped.

As we left the café, he pointed to an alley I had passed hundreds of times but never entered. “I live there,” he said. “Would you like to see?”

Again, this seemed the obvious thing to do, even though it was three in the morning. I had a lecture to give at eleven. But I followed him into the alley. It opened surprisingly into a small courtyard invisible from the street. In the centre stood a single tree—an ash, I think—and beneath it, a sort of nest made from cardboard and plastic sheeting.

“My palace,” he said with a gesture that was only half ironic.

He began to remove his coat. To this as well I surrendered. As he continued to undress, revealing a body covered in a pelt of grey-brown fur, I felt as if I were seeing, for example, desert flower that blooms at night, or an up to now undisclosed part of nature.

He seemed to have aged, longer in the face, longer in the tooth, redder in the eyes.

“Most of us are dead now,” he said, his voice broken, as if due to electromagnetic inference, but still intelligible. “Hunted or starved or simply unable to bear the slow mechanical death of the earth. I may be the last in England.”

“To what do you attribute your longevity?!

“Indigence” he smiled.

I nodded. All this information was perfectly obvious. He stretched and turned his face to the sky. Between the buildings, a perfect circle of off-white moon, turning the courtyard holy.

“You should go now,” he said. “But thank you for the coffee. It’s been a very long time since someone has spoken to me!”

I left him there, suffused in the calmest moon-wash, and walked home through streets no longer the same.

That night—or rather, that early morning—I slept more deeply than I had in years. I missed my lecture. I dreamed of running through forests; I dreamed of a different, powerful, body; an unpopulated earth.

I went back to the alley the next night, and the night after. I found broken bottles, cigarette ends, a single shopping trolley tipped on its side. Nothing was left of the den.

And no evidence of that encounter remains, except for the fact that from then on I can smell poetry

.